In acclaimed 2016 documentary “O.J.: Made In America,” Edwards explained Simpson’s reasoning for that stance, which took place during a tumultuous period of American history in which Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated and Muhammad Ali’s protest of the Vietnam War saw him stripped of his heavyweight boxing title and his freedom jeopardized.

“O.J. was saying: ‘I want to be judged, not by the color of my skin. I want to be judged by the content of my character and, most of all, the caliber of my competence,’ ” Edwards said in the film. “ ‘I think I’m the greatest football player that this country has ever seen, and that’s all I want to be judged by. Don’t tell me I’ve got to do this because I’m Black.’ ”

If anything, Simpson’s Blackness was something to be bartered — in exchange for wealth, for the fumes of White privilege and celebrity worship, for an escape from the realities he faced while growing up in the Potrero projects of San Francisco. His Blackness wasn’t supposed to be thrown in anyone’s face, to make the people who were cheering for him feel guilt for the indignities experienced in America by the people who looked like him. Mostly, his Blackness was to be avoided.

“For a lot of people who wanted to believe that they could applaud a successful athlete and not have to deal with any sort of racial politics, O.J. was their poster child,” Todd Boyd, USC professor and endowed chair for the study of race and popular culture, said in a telephone interview Thursday, after Simpson’s death at 76 of prostate cancer was announced by his family.

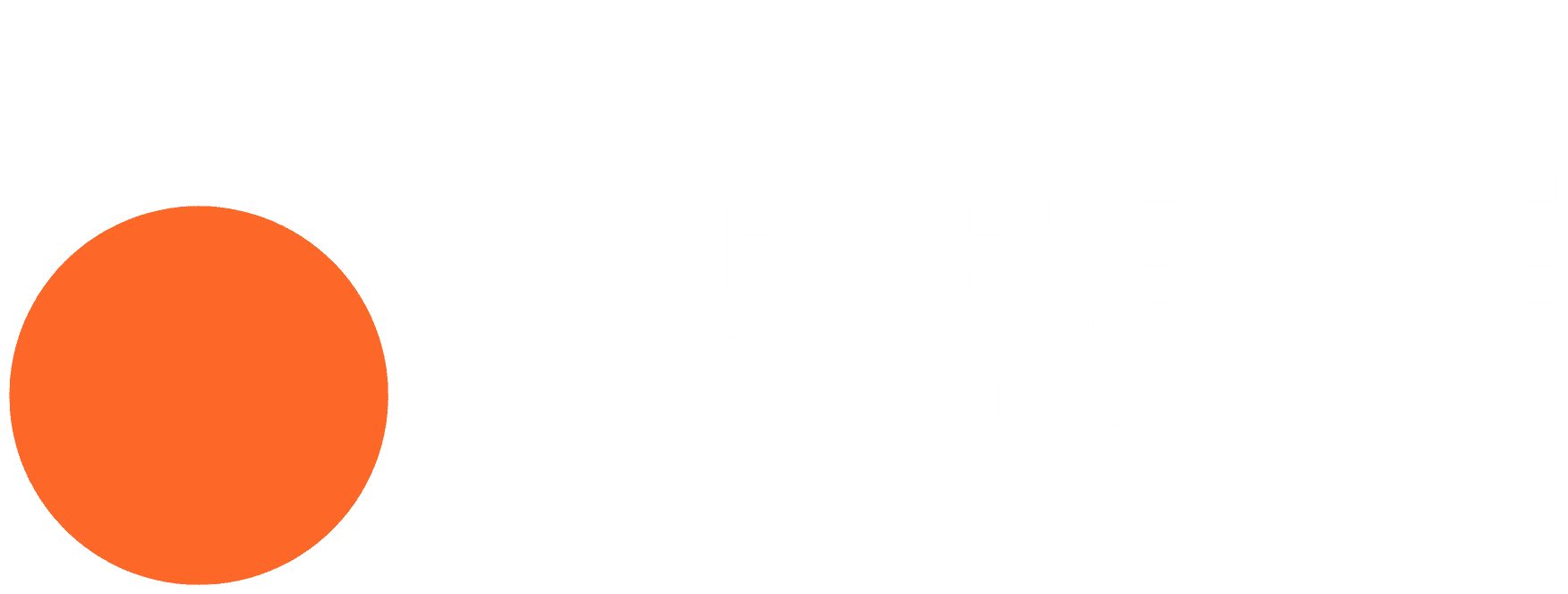

Simpson was the first post-civil rights sports icon. “A counterrevolutionary hero,” Boyd said. It wasn’t simply because of the talent that propelled him during that Heisman-winning campaign or in 1973 when he rushed for 2,003 yards for the Buffalo Bills. It was his smile, his laugh, his charm — all on display during television appearances and as he chased down Hertz rental cars in commercials to cheers of “Go, O.J.! Go!” It was the fact that he made White fans feel comfortable.

His decision to refrain from taking a stand on civil rights stood in sharp contrast to many star athletes of his era. Ali, Jim Brown, Bill Russell and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar comported themselves as if they believed activism was a necessary part of the assignment. Simpson sought social status over social justice.

In explaining his refusal to participate in the protest that Smith and Carlos engaged, Simpson spoke of the negative backlash they received, how it damaged their ability to profit from their success. He added, in an interview included in the “Made In America” documentary, “If I stand on a platform, I’m going to be speaking for O.J.”

Abdul-Jabbar, whose star turn at UCLA overlapped with Simpson’s time at USC, expressed Thursday night on social media his disappointment in Simpson’s approach. “Every Black celebrity knows that, whether they like it or not, they represent the entire Black community,” Abdul-Jabbar wrote. “Sadly, despite admirable accomplishments as an athlete, OJ Simpson was not able to live up to that responsibility. His life is a reminder of how quickly one’s legacy can crash and burn.”

Simpson put himself ahead of any movement or cause, changing the outlook for another generation of Black athletes who didn’t want to lose out on the money and professional opportunities that could come their way by speaking out against inequities and injustice.

“In a lot of ways, he was the ultimate individual, and America has always rewarded individuals,” Boyd said. “It’s when individuals identify with a group that things can become difficult.”

Simpson’s fall from grace remains startling because the plummet was so precipitous. The heights Simpson reached as a celebrity athlete, turned pitchman, turned broadcaster, turned movie star and then the depths to which his reputation sunk as a murder suspect were unfathomable. Where he was once loved, Simpson became hated and was never welcomed back, even after his acquittal in 1995 of the murders of his ex-wife, Nicole Brown Simpson, and Ron Goldman.

“It’s hard for a lot of people to remember who he was before the murder charges,” Boyd said. “He was not a hated figure. Maybe some Black people said he had sold the community out. Maybe. But I don’t know that people hated him. Maybe they were indifferent to him. But he was successful, and he influenced others. If you’re a young Black athlete, why wouldn’t you want to emulate what he had done?”

Interest in Simpson experienced a resurgence in 2016 with the FX series “The People vs O.J. Simpson,” starring Cuba Gooding Jr., and the “Made In America” documentary. That same year, Ali died and NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick’s protest of police brutality and racial discrimination became the most prominent example of modern athlete activism. In capturing the moment, Jay-Z released the Grammy-nominated song “The Story of O.J.” in 2017 and introduced Simpson’s famous words to a younger audience with a rhyme: “I’m not Black; I’m O.J. . . . OK.”

“O.J., to me, was always a hustler at a high level,” Boyd said. That hustle, he said, wasn’t geared toward the Black community, because it could “see right through him” and there was nothing to be gained from there. But White America “thought he was someone that ultimately he was not. For lack of a better phrase, they thought he was a good [n-word].”

Simpson might have been a mediocre actor, Boyd said, but he was superb in the role of O.J. — until his downfall revealed a different picture from the one that played for the cameras.

“It’s not a secret,” Boyd said. “O.J. is about O.J. — trying to do for self at the expense of everybody else.”