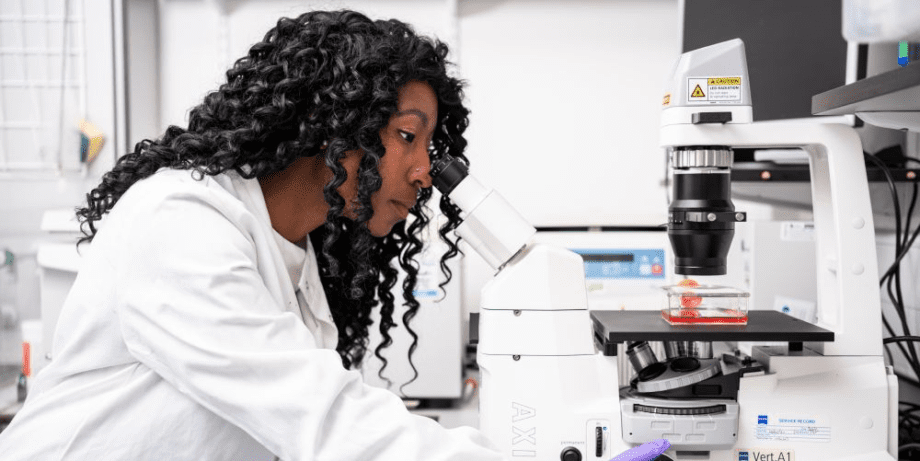

Sigourney Bonner (Human Physiology 2014) is driving change for black people, who are under-represented in cancer research and over-represented in cancer mortality.

Encouraged by her lecturers, when she graduated from Leeds Sigourney was determined to progress into medical research. The loss of her aunt to cancer made her more determined to change lives.

Sigourney ticked all the boxes for postgraduate research – a top degree from a Russell Group University, a year in industry, summer placements, a scholarship award for top performing undergraduates. Yet she wasn’t accepted onto PhDs, while fellow graduates with similar experiences were enrolled by the next term.

It took another four years before Sigourney was successful.

“Until I started my PhD, I’d never met a black woman with a PhD,” says Sigourney, who is now a postdoctoral associate at the Cancer Research UK Cambridge Institute. “I often felt I was the most qualified candidate, and yet I was at a disadvantage before I entered the room because of how I looked.”

Sigourney worked as a scientist at major pharmaceutical companies Pfizer and AstraZeneca before starting her PhD in paediatric brain tumours at Cambridge. Once there, she founded Black in Cancer, an organisation which helps to make sure the cancer research sector represents the wider population.

It was established at a time when social justice movements such as Black Lives Matter were helping to start conversations about spaces black people weren’t normally seen. “So I started to look at my experiences and my community,” says Sigourney.

With research also highlighting that black people – like her aunt – are over-represented in cancer mortality, Sigourney had two challenges she set out to address.

“Without visible role models, you might subconsciously narrow your options,” Sigourney says.

Although black role models in science were lacking, Sigourney “felt at home” at Leeds and was involved in a number of societies; she was vice-president of the Faculty of Biological Sciences Society, an academic representative, and a mentor. “I realised that I’ve been creating inclusive communities since I was an undergraduate. Leeds truly gave me that sense of activism and the ability to change things.

“I was introduced to neuroscience labs by Leeds lecturers who then encouraged and supported me, and that’s why mentors at Black in Cancer can be from any background – so long as they have an awareness of the challenges the black community faces.”

Black in Cancer’s pipeline programme helps to increase black scientists in the field – from undergraduate mentorship and lab placement schemes, to distinguished investigator awards for established principal investigators. They have built partnerships with universities and research organisations in the UK and the US, created a conference series, developed a mentorship programme, and helped black researchers access over £1.5m of funding.

The individual stories tell me that the work is making a difference.

The second focus of Black in Cancer sits closest to Sigourney’s heart: “My aunt didn’t know what kind of breast cancer she had when she died. I didn’t know either. Black patients don’t always advocate for themselves or ask the right questions because it’s such an overwhelming experience.”

A study by Cancer Research UK and NHS Digital found black women were more likely than white women to be diagnosed with late-stage cancer. Research by the Race Equality Foundation also found black patients reported more negative experiences of cancer care than white patients. “The reasons are complicated. It can be because individuals are unwilling to take time off to see a GP because of financial implications. There may be a lack of awareness about warning signs, embarrassment or a lack of confidence talking about symptoms.

“But also black voices are sometimes not heard. Referrals to oncologists can take longer – often three times as many visits to a GP for those from ethnic minority backgrounds. Many give up in that time.”

The Black in Cancer team run awareness seminars within communities. They have cancer survivors describe their experience, clinicians explain diagnosis and treatments, and researchers talk about work in the lab. Social media programmes help to get rid of myths around cancer, and increase diagnosis and testing.

Four years in, and already the impact has been greater than Sigourney ever imagined. In 2021 she was named in the Forbes 30 under 30 list for her work in science and healthcare. But despite the wide-reaching impact across the UK and the USA, it is the individual stories that mean the most: “Students telling us a placement changed their life, or patients saying we’ve helped them find a support group, that’s the important bit for me.

“The individual stories tell me that the work is making a difference.”