Editor’s note: While Ayeyi Asamoah-Manu serves on the board of the African Students Association, Asamoah-Manu was not involved in the organization of the event.

It was 7 p.m., on a Friday night — Nov. 15 2024. And while it was more like 59 than 95 degrees on that crisp November night, the temperatures in the Trotter Multicultural Center had risen to rather unprecedented levels. Here, the African Students Association at the University of Michigan, in collaboration with its counterpart at Eastern Michigan University, put together a game called “Pop the Balloon or Find Love,” a simulation of the viral sensation YouTube show that brought contestants together and gave them one singular task: Pop the balloon or find love.

Although many variations exist across different countries and sexualities, the most popular version is led by the indelible, gorgeously dressed but always slightly messy, Arlette Amuli. I use the word messy here to mean a little outrageous, a little out-of-pocket but altogether, very comedic. The Arlettes — or rather, starlets — of the University of Michigan reprisal were Ayomide Fadase and Mogbonjubola Adepoju, who kept the audience riveted and engaged throughout the night.

The premise of the game is simple: single bachelors or bachelorettes stand in line holding bright red balloons. Then eligible partners would step in and answer a series of questions, including name, age, romantic interests, pet peeves, and the like — you know, quintessential, romantic, reality TV questionnaires. The hosts would then ask a series of follow-up questions, to give the audience and the other contestants a greater glimpse into the speaker’s life. Questions such as what they looked for in a partner, red flags, and dealbreakers, revealed each person’s personality and, to a deeper extent, their perspective on love.

Then, the balloons go off. One by one, intermittently, spontaneously. Some, to the most obnoxious things like mismatched toenails or the likeness to a Ninja Turtle. Others pop to deeper, more reasonable explanations, like differing cultures, disagreements on love languages or compatibility. Regardless, if a red flag is found, a red balloon is popped, signifying an elimination from the show.

What follows forms the crux of the night. The hosts quite literally saunter around the room, asking decliners why they popped the balloon and if the person was originally their “type” or not. Then, as if the show could not get any more outrageous, if many balloon holders remain, participants could then pop the balloons of those they wish to eliminate.

Like I said — messy.

Indeed, the palatable awkwardness of the show is what makes it so entertaining. Contestants have to audibly voice why they rejected another participant with no voice or mask to hide behind. Arlette herself describes it as “kind of like a dating app, but in real life,” with no witty Tinder caption or no quirky Bumble selfie to hide behind.

The show’s structure also immediately delves into preferences in partner selection, often prioritizing physical appearances, core values and relationship goals over the small talk about one’s major or favorite artist that college students have come to expect on the first date.

In a post-event interview with The Michigan Daily, both hosts were eager to explain this more deeply.

Mogbonjubola Adepoju, the vice president of the student organization and co-host of the live show, explained: “In just one hour, participants find love, share laughs, and exchange diverse perspectives on what people value in partners within our community. I think it’s a fantastic concept, especially for college students who often find themselves too busy to meet new people.”

Ayomide Fadase, who serves as the event coordinator for the student organization and co-host for the night, echoed similar sentiments, describing “Pop the Balloon” as “a fun and intriguing concept that the black community enjoys (because) we love to hate it.”

And I would have to agree. Frankly, there is no polite way to pop a balloon; it will be awkward, brutish, and a little crude, but at some point, it has to be done. And it makes for damn good TV.

But it got me thinking, is Pop the Balloon really setting the Black community back as many people think? Is the blunt approach that is so characteristic of reality dating shows too demeaning or superficial to facilitate real love? Is the format of lining young, Black singles and rejecting them with a pop of a balloon too similar to a live auction, trading the sacredness of Black Love for a cheap laugh?

From observing current media culture, it’s clear that Pop The Balloon has become well-loved by Black audiences, who both feature predominantly in its cast and consume its weekly episodes. Discourse on social media such as X and TikTok are often pioneered by Black web users and consumers, whom the show seems to primarily attract and engage.

Many argue that Pop The Balloon’s popularity stems from the frustration regarding the lack of diversity in traditional dating shows. In response, Black content creators and consumers have created this web series – an outrageous, wild and slightly absurd TV show — that they feel, in some way, accurately represents their community.

No doubt, the show offers a reality TV escape that is wholly and unapologetically, Black. It is made by Black creators, often featuring an all-Black cohort of contestants, a Black host, and primarily consumed by black viewers. Like the phenomenon of Black Twitter, now Black X, “Pop The Balloon” serves as a space where young, Black, eligible singles can go to find love while being their unapologetic, slightly problematic selves.

“Thinking about the Tyler Perry franchise, for example, there are so many things that are controversial and wrong about the franchise.” Fadase adds, “But we do see some elements of ourselves in that. I think the same goes for Pop the Balloon. These are real-life things happening (to) real people, and the fact that we can connect, even on a controversial level, helps to bring the people together.”

But by bearing all this to the world, the infamous show finds itself subject to critique. As Medium writer Faithe J Day cleverly states, these series can teach in depth about “desirability, sexual identity, Black Nationalism, and the differences between race and ethnicity,” It bears the intricacies behind the definition of love and desirability within the Black community for the world to see, exposing us in our best and our worst, in our flaws and all.

Thus, for a show that, quite frankly, reveals deep characteristics of our community — what we consider attractive, how we interact with each other, whom we desire — and places them on a pedestal for public consumption, we must be quick to question if it is indeed the right mirror we need to be out there.

As with any other reality dating show, conventional beauty standards always find a way to rear its ugly head. Male contestants on the YouTube show chiefly expressed their preference for lighter-skinned women who were fit, curvy or slim-thick, while women expressed a desire for tall, physically fit, darker-skinned men — revealing the strongholds of colorism and toxic masculinity that reside within the Black community. Contestants have revealed even more ridiculous beliefs, popping their balloons for contestants who were “too African”, had a stocky build, or had awkward knees, with each episode seemingly getting more outrageous than the next.

It is also not lost on me that, due to the virality of the show, many contestants sign up simply to network, gain business partnerships or amass a larger online presence. Evidenced by many contestants who just reveal themselves by their Instagram handle or stage name, (the episode featuring James who only introduced himself as James from James Gourmet Pies serves as a pertinent example), it proves that the goal is no longer to find love but simply to gain clout, leaving the show an empty shadow of the very purpose it intends to accomplish. And what’s more, this new form of social climbing does so in ways that play and prey on Black stereotypes and politics— thus, setting us back, as many critics concluded.

With Black creatives on the rise, many also worry that any misstep would set us in the wrong direction. In an age where the Black community at the University itself seems to be healing, from the election, a white lives matter protest, and the constant weight of being Black at Michigan, there were fears that this event and the show itself would set us back in a time when we needed to be united the most.

And yet, from what I observed, it was clear this was the type of relief the community needed. Watching as the entire Trotter Basement filled, I saw the event imbue a sense of community I had not seen in months. In fact, many people I interacted with described the event as well-planned and wildly hilarious, a sentiment I myself shared as I watched from the sidelines. The event’s healing impact on the University’s Black community was undeniable: a fan club forming for one bachelor, uproarious laughter filling the room, and two couples ultimately pairing up all demonstrated the event’s power to unite and uplift.

“At Black UMich, there has been a noticeable drought of fun and engaging events this school year,” Adepoju explained. “Pop the Balloon” is helping to bring back the vibrant energy that many of my friends and I remember—an atmosphere where the campus was alive with dialogue, excitement, and opportunities to mingle. This event is a step toward revitalizing the sense of community and connection that makes Black UMich feel like home.”

So to the question of whether Pop the Balloon harms the Black community, I argue that the answer lies in the intention behind the organizers and the community itself. If contestants are truly participating to find love, and not satisfy some economic or social aspirations, and if the organizers are truly seeking to create space for Black couples to meet and find love, “Pop The Balloon” could be a true cornerstone for the Black community.

“At first, it was seen as a way to divide the black community because it’s so outlandish and risque,” Fadase explains, “but I think when deciding on planning, I just wanted to bring the community together, and I think Pop the Balloon definitely did that.”

So to those who criticize the central concept of the show, arguing its outlandish nature paints the Black community in a deeply negative light, I sympathize with you. I truly do. Without that intentionality, we are left with the situation we see in many YouTube videos today, where our community is left as disjointed and fragmented as the red latex balloons we watched pop before us.

To that nature, however, I will also argue that Black audiences deserve the same opportunity to enjoy and relate to dating shows, even in their brazenness and outrage. “Pop the Balloon” is no more absurd than mainstream reality dating shows like “Love is Blind”, “The Ultimatum” or “Love Island.” These shows are intentionally excessive, which is what makes them compelling and wildly entertaining.

Black viewers should have the chance to see themselves represented in such entertainment, reflecting on both the positive and negative aspects it portrays. When executed thoughtfully, as in Arlette’s version or the recent ASA adaptation, “Pop the Balloon” can truly bring people together and spark joy. This powerful effect shouldn’t be dismissed.

Ultimately, Black audiences deserve a space to express themselves fully and embrace all we are, even in our messy, wild, fantastical glory.

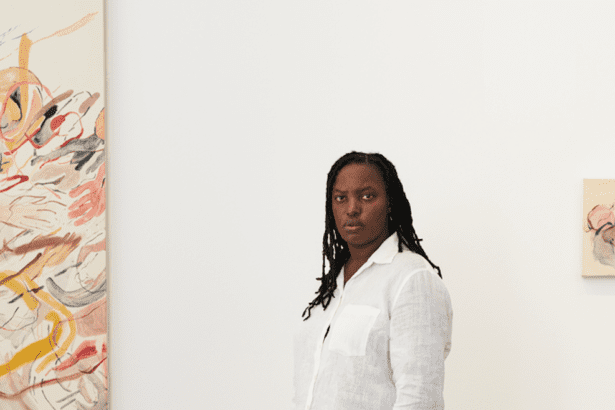

MiC Senior Editor Ayeyi Asamoah-Manu can be reached at [email protected].