By Merdies Hayes, Editor | Our Weekly

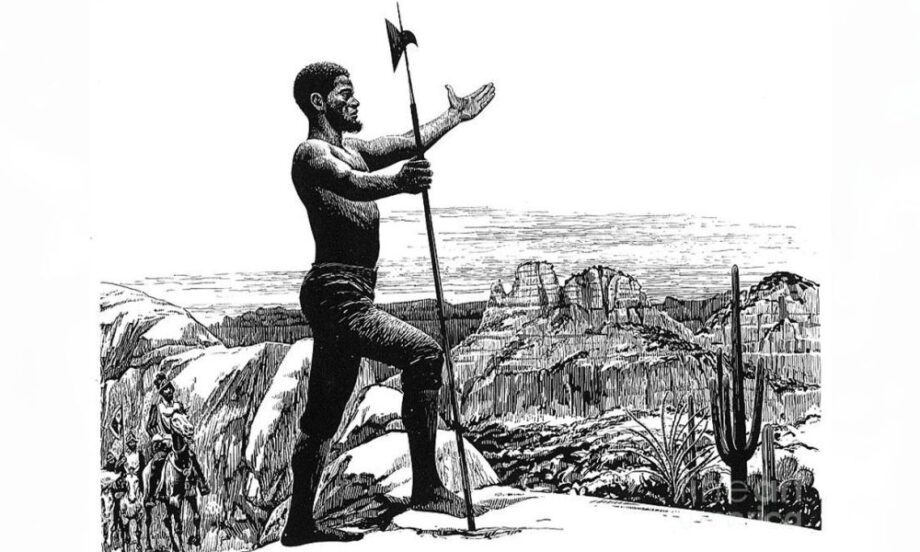

The history of slavery in the Western Hemisphere has, of course, been well documented but there is one name that is often overlooked in within the posterity of Black people in the New World: Estevanico.

Sometimes called “Mustafa Zemmouri,” “Black Stephen,” “Esteban the Moor” or “Steven Dorantes” (after his owner Andres Dorantes, a Spanish nobleman), Estevanico was a member of the Panfilo de Narvaez 300-man Spanish expedition which arrived in April 1528 near present-day Tampa Bay, Fla. The expedition was largely doomed from the start. This was not uncommon among the list of Spanish conquistadors who ventured to the New World seeking fertile land and untold riches imagined from the artful tales of Giovanni Verrazano who explored the northeast, Cabeza de Vaca in the Gulf of Mexico, Hernando Cortes in Mexico, Hernando de Soto near present-day Florida, and Francisco Pizarro far south in Peru.

Who was Estevanico?

Chroniclers from the 16th Century, who were contemporaries of Estevanico, considered him a Negro. However, modern historians claim he was descended from the Hamites who were White residents of North Africa. According to this theory, Estevanico could not have been Black. Historian Caroll L. Riley has asserted that Estevanico was “Black in the sense that we would use the word in modern America. Actually, in modern generic terms I suspect that Estevanico was very mixed.”

Riley also explained that if Estevanico was considered a “Negro,” his mixture must have been mainly Black. Estevanico in 1513 was sold into slavery to the Portuguese in the town of Azemmour, a Portuguese enclave on Morocco’s Atlantic coast. More contemporary accounts have referred to him as an “Arabized Black” or Moor, the latter term often used for Berber natives. History primarily refers to him as a Black African. A Spaniard, Diego de Guzman, reportedly saw Estevanico in 1536 and described him as “brown.”

Estevanico was reared as a Muslim—with some accounts of him converting to Roman Catholicism—but there is little historical account of his religious conversion.

The natives of one tiny island off the mainland coast (Galveston Island near Texas), encountered a strange sight in 1528: A band of emaciated White men lying naked and near dead on the beach. This group, in large part, was what was left from Narvaez’ expedition with de Vaca serving as its treasurer. Narvaez dreamed of riches when he reached the Florida coast and after finding mere traces of gold, he split the group and dispatched the ships toward the River of Palms (today’s Rio Grande) and took the land force toward a reportedly “rich” city brimming with gold and silver called Apalachen (near Tallahassee, Fla.).

A doomed expedition

Instead of finding their heart’s desire in wealth, the only things encountered in the Florida Panhandle were naked Native Indians, low supplies of food and even less game. The 260-man party lasted two weeks in this region, and eventually set out on makeshift boats with sails made from clothing. This was a fateful mistake. There was practically no food left or fresh water to drink. After constantly bailing water from their rickety crafts (and forced to drink salt water), only a few people survived and made it to shore. Narvaez was lost at sea.

Cortes, for his part, had listened faithfully to these “tales of riches” but found neither a queen called “Califia” nor gold and pearls along the west coast. He did, however, step ashore onto what he believed to be an island (Baja California) finding neither riches or fertile land, but would claim the land for the Spanish crown.

Cabeza de Vaca eventually made it to Mexico with only three men, among them Estevanico. There they recounted the horrors of slavery, starvation, cannibalism and disease which took the lives of 90 men. They reportedly posed as shamans, crossing the land curing sick Indians and attracting quite a following in being labeled “children of the sun” because of their long journey from the east. By the spring of 1529, those four men had traveled on foot along the Texas coast to the environs of Matagorda Bay (about 80 miles northeast of Corpus Christi) only to be captured and enslaved by the Coahuiltecan Indians. Six years later the four men managed to escape their bondage and entered Mexico.

Arriving in Texas

Estevanico was assuredly the first African to traverse Texas. In fact, historians believe he was the first African to visit the indigenous people of Mexico and may have reminded the inhabitants of the ancient sculptures of the Olmec civilization in Mesoamerica (1200-900 B.C.) which depicted persons with Black facial features. Estevanico, by extension, may have been considered by the native population as a descendant of the gods. Some writers have claimed that the Olmecs were related to the peoples of Africa, based primarily on their interpretations of said facial features, even contending that epigraphical and osteological evidence may support their claims. Further, some researchers have claimed that the Mesoamerican writing systems are related to African script. To date, however, genetic and immunological studies over the decades have failed to yield evidence of precolumbian African contributions to the indigenous populations of the Americas.

By 1539, Dorantes had either sold or loaned Estevanico to Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza, who later assigned him to the company of Fray Marcos de Niza, the latter charged with leading a follow-up trip to the region of the failed Narvaez expedition. In a strange coincidence, Estevanico and others were surprised to encounter de Vaca near present-day San Antonio, Texas. By then, de Vaca had been working as a trader among the various Native Indian tribes. They resided in that region for about four years with Estevanico working as a shaman or medicine man versed in several Native Indian languages and also demonstrating his prowess as a seasoned explorer.

Estevanico must have been a strange sight to the native peoples. He rode around with a special gourd trimmed with owl feathers that signified his status. He reportedly had an entourage of some 300 natives, kept two Castillian greyhounds as pets, and possessed a special “medicine” wand with bells affixed to it said to ward off (and supposedly cure) various diseases. He also carried with him special plates made of turquoise specifically for his meals. He even had a special lodging constructed fit for a man of his stature.

Dreams of untold riches

Like the others before him, Estevanico was consumed by discovering the Seven Cities of Gold. His ultimate goal was to reach one of the seven famed cities of Cibola (near modern Zuni, NM) which was said to have streets paved with gold. When Estevanico and his entourage arrived at Hawikuh, a Zuni pueblo made of stone buildings several stories high, he expected to be treated as the man of stature he’d become accustomed to.

But the Zuni’s didn’t trust him. They especially disapproved of his gourd covered with owl feathers which were a symbol of death to that tribe. Also, his rather unusual stories about great White kings from far away further drew suspicion among the Zuni tribal leaders. There are two general accounts surrounding the fate of Estevanico. In one scenario, the Zuni people decided he was a spy (or simply a fraud) and killed him. Some accounts contend that he offended the Zuni people so much that they staged three executions eventually cutting up his body into little pieces. A second theory is that the Zunis didn’t kill him and that Estevanico staged his own death with the help of his allies, therefore finally gaining his freedom from slavery. The latter theory is supported by the fact that his body was never found.

His mysterious demise

The Zunis were asked why they killed Estevanico and they said that he claimed a huge army was following him with weapons meant to kill their tribe. Several of his Native Indian escorts reportedly escaped from the Zunis and returned to Mexico to inform Fray Marcos that Estevanico was dead. In his report to Viceroy Mendoza, Marcos said that he continued to travel north to at last enter Cibola (or Hawikuh) and upon arrival he witnessed a chief with Estevanico’s turquoise dinner plates, his two greyhound dogs, and his famed “medicine” bells.

Irrespective of his demise, Estevanico is one of many historical figures of color who manipulated their situation to move between cultures and transcend their humble beginnings. His is a true story of transformation from a slave to a man of legend evidenced by the Zunis memorializing him in a black ogre kachina (a doll measuring about a foot high with protruding teeth, a black goatee and black facial paint) which they called Chakwaina.

A legendary adventure

The tale of Estevanico is more than a story told in the oral tradition. Often, the history and contributions to society by Black persons prior to European settlement in the New World are considered less authentic and reliable in terms of literary content because it was believed Blacks did not ascribe to a written language. Estevanico did not write a diary or narrative of his exploits.

However, two small thin volumes of literature provide a wealth of information about this early explorer. John Upton Terrell published “Estevanico The Black” in 1968 and at only 115 pages, it ranks as one of the most informative books about an extraordinary figure who doesn’t always receive due attention in secondary education. In 1974, “Estebanico” was issued by Helen Rand Parish. Even smaller than Terrell’s book at 128 pages, she wrote that Estevanico could be considered “new historical history” particularly for young readers.

Also, “The Moor’s Account” by Laila Lalami (2015) provides a more fictional account of Estevanico. The author created her own back story about the events that led up to his enslavement and then fills in gaps of what we know about the Narvaez expedition that would eventually place Estevancio’s name in the history books.

No one knows where Estevanico is buried. Hawikuh no longer exists, having been abandoned in 1670 following a series of wars the Zunis fought against the Spaniards and the Apache. But Estevanico’s story, recorded in colorful detail by his fellow explorers Cabeza de Vaca, Fray Marcos, Coronado, and Pedro de Casteneda, endures as one of the great adventures in American lore.

Post Views: 3,649