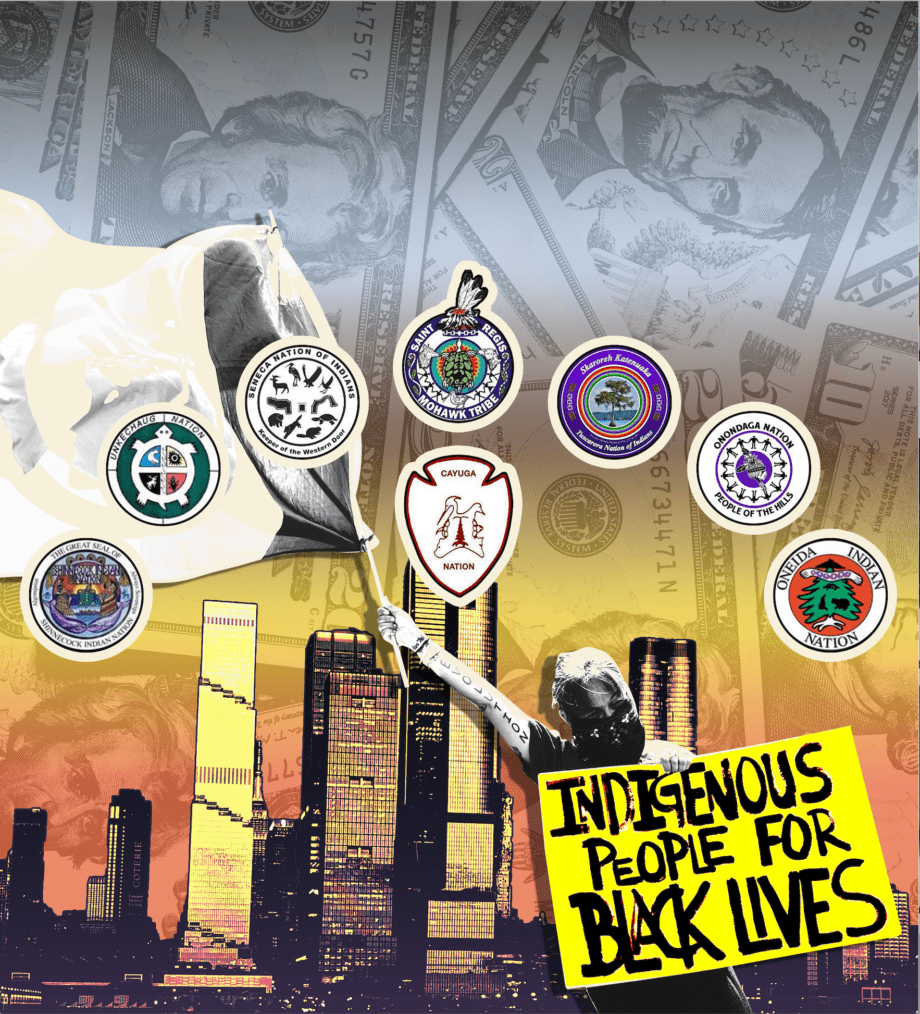

A new report from the BLIS Collective says that when Black and Indigenous groups combine their interests, it strengthens the push for reparative justice.

The Black Liberation-Indigenous Sovereignty (BLIS) Collective, a new organization created in 2022, will issue its first report in January 2025. The study, titled “Fabric of Repair: The Impact of Braiding Narratives of Reparations and Land Back on Black and Indigenous Audiences,” reveals that while Black and Indigenous communities often prioritize their own issues, they are also likely to support each other’s reparative efforts when provided with sufficient information.

BLIS wants to get that sort of information out by promoting narratives that illustrate the connection between settler colonialism and the exploitation enslavers used against Black people. The organization sees itself as “a solidarity and action hub that braids narratives and grows movements,” said co-founder/executive director Trevor Smith.

“How BLIS was born was my co-founder, Savannah Romero — we met in grad school — (and I) were at a party one day, just kind of talking about our work,” Smith told the AmNews. “The conversation kind of got to the place of asking ourselves, why isn’t the Black land movement for reparations and the Indigenous land movement for Land Back more connected? They didn’t feel as connected as we thought they should be, despite obviously not the exact same histories, but similar goals that relate to repairing the hurts caused by colonization and the transatlantic slave trade.”

Anti-Indigeneity and anti-Blackness

The Black reparations movement and the Indigenous Land Back movement have each had to overcome crippling societal efforts to destroy them. Mainstream U.S. culture is based on a history that justified genocide, land theft, and the violent pursuit of wealth –– the basic tenets that support anti-Indigeneity and anti-Blackness, the BLIS report contends.

After trying to exterminate Native Americans, the United States simply sent them to live apart from the rest of society. “The resulting invisibility of Indigenous experiences in mainstream discourse has led to widespread public apathy toward Indigenous rights and justice,” the report states.

“A 2018 survey found that 72% of Americans ‘rarely encounter or receive information about Native Americans.’ People cannot mobilize or advocate against a problem that they aren’t aware of, which is what makes the erasure of Indigenous people such an effective narrative tool for those looking to hoard power, suppress challenges to a white supremacist status quo, and manipulate ideals such as democracy and freedom to legitimize inequity and maintain dominance within social and political systems.”

Anti-Blackness, the report also says, is regularly evidenced by police violence, the perpetuation of the Black-white wealth gap, and the “depressed … social, economic, and political power of all Black people [that] has grown on the backs of Black women.”

Slavery and colonialism connect our stories

Indigenous and Black activists share an interconnected history, yet they don’t often associate their struggles. The BLIS report calls on activists to show “visible and vocal solidarity” with each other. Doing so can change the dynamics of how reparative justice efforts are responded to by the larger society.

As part of the report, BLIS surveyed 2,886 people, looking for their responses to videos that spoke about either the Reparations movement, the Land Back movement, or both movements at once.

Smith said that BLIS couldn’t predict which kind of videos would be most popular. “We really wanted to get a baseline understanding of how much support exists between Black and Indigenous communities on the topic of Reparations and Land Back, and what the effects would be when we produce the video that talked about both of these movements and the interconnectedness of these movements.

“We found that the video that braided the narratives together was effective at increasing support for Reparations and Land Back within Black and Indigenous audiences.”

One video the organization recently made has social media content creator Garrison Hayes talk about the United States’ two original sins: “… This land belonged to indigenous people,” Hayes says about a plantation just outside of Nashville, Tenn., that was once owned by Andrew Jackson.

“In fact, this region was home to some 600,000 indigenous peoples, including Cherokee, Chickasaw, and Shawnee people, but between the years 1492 and 1900, European settlers stole more than 1.5 billion acres of land from Indigenous peoples across what is now the United States. And at the same time, those settlers were building America’s wealth on the backs of enslaved Africans. By 1860, the value of enslaved people was estimated to be between $3.1 and $3.6 billion: an amount more valuable than all of the railroads and factories in this country at the time –– combined.”

Efforts to combine Black and Indigenous narratives will be long-term and generational — the kind of work that will be necessary to build solidarity. The growing national effort to fight for Black reparative justice policies is mostly taking place on the local level. Places like Evanston, Ill.; Los Angeles, Calif.; Boston, Mass.; Kansas City, Mo.; and New York State are studying the idea of reparation programs for Black Americans. As they build locally, these programs can note how Land Back and Reparations ideas work together.