Reviewed by By Michael Washburn

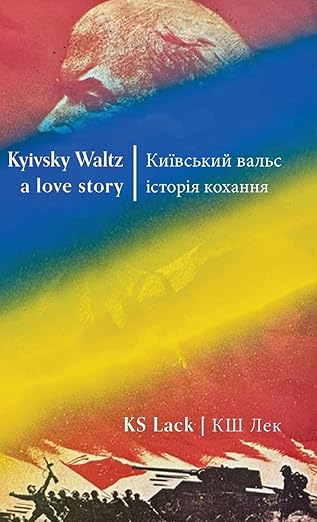

A review of Kyivsky Waltz: A Love Story

By KS Lack

Finishing Line Press

Feb 2024, 27 pages, Paperback, ISBN: 979-8-88838-468-8

Ask people today to describe what they imagine to be a typical street scene in Ukraine, and many will fall back on certain stock images. Rubble. Rocks. Dust and dirt. Splinters. Shredded tires. Fissures in the earth. Loose trash. Ravenous strays. Blood and guts. The forgotten shoe or hat of someone in a hurry to get away. The corpses of those not yet buried. Heaps of them. Or, depending on the circumstances, jackboots and tanks on the move from one point in the dreary day to another, with still more horrific violence to come.

For a young American woman with a deep personal interest in her Jewish and Eastern European heritage, the history and literature of the region, and the complex intertwine of personal and national fortunes, Ukraine, and Kiev in particular, held out a montage of entirely different images for a time in the mid-1990s. Writer, poet, and letterpress artist KS Lack, who lived and worked in Kiew from 1994 to 1996 after graduating from Columbia University, has assembled a record of her thoughts and impressions of that period in the chapbook Kyivsky Waltz: A Love Story. Her medium is poetry, the prose poem, and the letterpress image.

Who or what is the object of the love referenced in the title? In the course of this brief book, the reader experiences a Ukraine utterly different from the one of today’s headlines, through the eyes of a sensitive, curious, romantically inclined transplant eager to see beyond the cliché of an impoverished, failed state still mired in collectivist backwardness. We accompany Lack on this journey, from her arrival in September 1994 through a sequence of events including her ride up Chkalova Street in a car her editor has dispatched; foraging for food in a market that looks and feels utterly different from any she has seen before, and from which she retrieves wine and what she believes to be cookies; finding solace in the company of a cat named Trotsky; meeting with a rabbi who turns to be a fellow New Yorker and Yankees fan; and her encounter at a party with a young man whom others have described as “a musician masquerading / as an English teacher / fluent in Russian.” From Lack’s description, the reader’s impression is of a guy decked out in attire even more awkward than Mr. Darcy, he of the notorious reindeer sweater in the film Bridget Jones’s Diary. He wears “second-hand dickies / and a mustard yellow / ski sweater so awful / it had to be ironic.”

Indeed. This is a land where the most seemingly dreadful circumstances suggest a critical perspective on themselves. The “awful” sweater is ironic, and far from turning her off, the young man Lack meets at this party will come to play as direct and essential a role in her emotional, intellectual, and spiritual life as the haunted spaces around her.

The reader senses that the meeting could not possibly come at a more opportune time. For the fish out of water narrating this chapbook, the crowding of rooms and the polyglot character of gatherings does not preclude feelings of isolation, alienation, or the need for contact more rooted and permanent than strangers rubbing elbows in rented rooms tend to achieve. In the prose-poem “Notes from a Passover,” Lack describes the scene in an apartment: “Languages fill the air, dancing together in a swirl of cigarette smoke. We sing our praises and the thread binding us together thrums. These prayers have been spoken here before; they will be said again when I am gone.”

That thread binding the guests together may be a welcome thing, but its temporary nature, and the contrast between that party and later scenes in Lack’s own life and the national experience of Ukraine, could not be starker. Meeting a young man who shares something of her sensitive, curious, intellectual character marks the start of an adventure which Lack renders as only a well-read and naturally gifted poet can. “Victory Day” describes a journey that, in uniting universal aspects of train travel and those unique to Ukraine, brings Lack and the man she has met ever closer together in a shared feeling that they have gone beyond the kitschy experience of tourists and really come to know something of this foreign dreamscape, and of each other. “Wrapped around one another we read / and dream as the train lumbers along / rolling by small dusty platforms as / Babushkas cry their wares to our / windows, slip back into darkness / disappear.”

The two lovers go on to walk through “streets hungover from days of glamour” and to hear, in proximity to the Battleship Potemkin, Odessa’s clocks striking noon. They have come to attain a certain intimacy not only with their adopted homeland but with the strange, foreign land that each of them initially was to the other. “Joy pours from my mouth, washing / the world in blue. This is what it / means to love you.”

It is a testament to Lack’s artistry that she has no need ever to identify that point in the cavorting and traveling when she and the young man cross the line and attain inseparability. Soon enough, they and the reader know. This quality leaps from a number of the later poems, in which Lack addresses her lover never by name but as “you.”

The power of this bond informs the short “Yom Kippur,” in which, on the young man’s return to the city, Lack wants to vent at him for having gone away, but her faith in the strength of what they have forged stays her hand. It also manifests itself when the figurative shoe is on the other foot, and Lack is back home in Northport, New York, late at night, missing her lover, with only a clock for company “whose red / digital glow never / seems to change.” She imagines the object of her devotion traveling east on a train in that other country, on a day whose chill “burrows into my heart.” She expresses her trust in him along with her concern about the fragility of a trust “no match for / that night when even the / clocks have stopped.” In some of the most resonant lines of this chapbook, Lack seems to convey a truth not only of this relationship but of her having lived with chronic pain from a young age: “Pain and I are cellmates / hurting like this is new.” Then the phone rings, and Lack decides to let it ring on, to “hear the / silence that surrounds it,” until she picks it up, and in a poetic sleight of hand, he answers.

To accompany Lack on the journey of Kyivsky Waltz is to follow the arcs of two inseparable love stories, to fathom the depths of her passion for another human being and for Ukraine as it existed before the calamities of the present and as it still exists, outside time, in the mind and soul of a gifted poet.

About the reviewer: Michael Washburn is the author of The Uprooted and Other Stories, When We’re Grownups, and Stranger, Stranger. His short story “Confessions of a Spook” won Causeway Lit’s 2018 fiction contest, and another of his stories, “In the Flyover State,” was named a Distinguished Mystery Story of 2014 by Best American Mystery Stories.