After dark, last year, we all heard an unforgettable din: the sound of helicopters patrolling the night sky; adrenalized masses chanting in protest against the state’s anti-Blackness; a video, left eerily on loop, of George Floyd’s horrible plea for oxygen and kinship. As a sort of private respite, I turned to gospel. I’d grown up in, and come to reject such Baptist zeal but could not deny that the music in particular would always and forever stir a prayer in me. I recalled my father’s commentary on the nights I self-soothed to Mahalia Jackson or the Staple Singers: “Listen close. Prince, Michael, Chaka Khan, Little Richard—it’s the same beat you hear at church every Sunday.” The greatest contributions our people had made to the world were the devotional songs from which most of American popular music sprang. Now, in its insistence on that beat, Black performance in latter-day America seemed to bear a literal pulse that located its origins not merely in life as such but in the habitual, righteous, and even miraculous defiance of death.

In his new collection of essays, A Little Devil in America, the poet and critic Hanif Abdurraqib surveys this sprawl of expression. Here he charges himself with quite an ambitious task, pinning down and contextualizing the historic scale of such a globally significant cultural output, and it is one that would appear to call for an equally ambitious scope: the book bears the casually panoramic subtitle “Notes in Praise of Black Performance.” Praise, of course, invokes religious ecstasy and thus highlights the centrality of worship and ritual to the inventive African American artistry that he beholds so lovingly. The usual subjects of such a study in performance attract Abdurraqib’s searching eye. Contemplations of legendary voices, sleights of hand, and charismatic choreographies are in dialogue with his own stories of grief, love, faith, and the search for freedom within the confinements of borders and a body. It is fitting that Abdurraqib opens the book with a consideration of the dance marathon craze that enthralled Americans in the 1920s. Though James Baldwin theorized that only music could really capture Black America’s story, the physical endurance that dance marathons required makes a tidier metaphor for such improbable survival. “What is endurance to a people who have already endured?” Abdurraquib writes. “What is it to someone who could, at that point, still touch the living hands of a family member who had survived being born into labor?”

Alongside these disciplines, Abdurraqib expands the conception of “performance” to include the whole realm of behavior and culture. The theatricality of bluffing at a game of spades is a production all its own, and one that I recognized from nights when my mother entertained a cousin or two at the kitchen table; yet another domain of performance is Black masculinity and its heartbreaking negotiation of love and violence, which Abdurraqib depicts, skillfully and tenderly, toward the book’s finale. Indeed, when seen from this vantage, Abdurraqib’s meditations on performance could extend ad infinitum. In his mind it becomes not so much a discrete event or object but rather any attempt to bridge the questions who am I? and what could I someday be, and who will be there with me? That bridge is life itself, and one walks across it until one grows insensate, abandons the company of others, or otherwise reaches the other side.

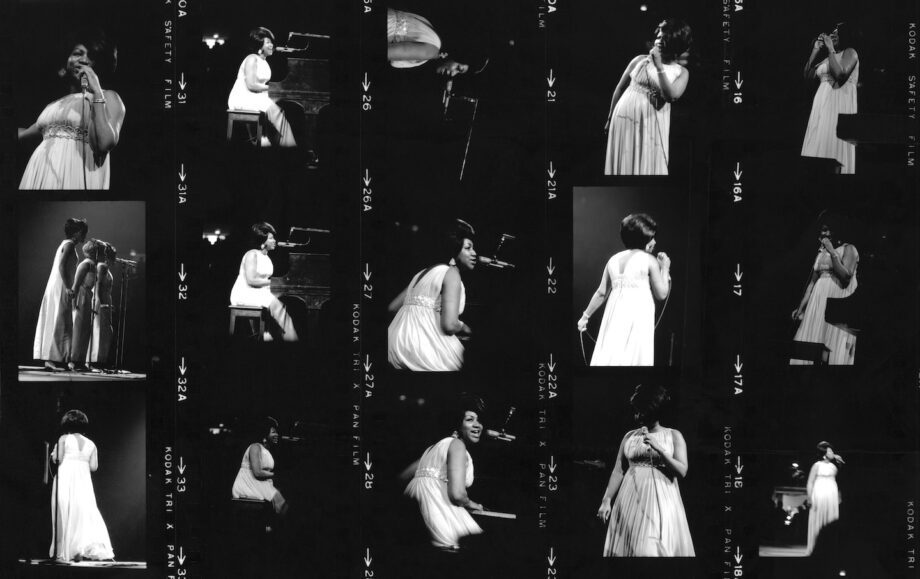

Even after such lengths are crossed, encores continue to impress. In one early piece, “On Going Home as Performance,” Abdurraqib considers the rituals of death as a sort of stage exit. The sedate Islamic funerals of his youth contrast with the dramatic publicized homegoings of Aretha Franklin and Michael Jackson. Abdurraqib takes these memorials as evidence of Black Christendom’s peculiarly baroque tendencies, although any artist of significance might make a spectacle of death—the release of David Bowie’s Blackstar comes to mind. Still, Abdurraqib displays a poignant awareness that the excesses of Black expression—so relentlessly mistrusted, classed, and yet envied by everyone outside it—in fact resolve into a participatory and imaginative vision of personhood. No sequence of actions develops into performance without an audience to receive it, and Abdurraqib relishes the possibility inherent to such a relationship. This sensation, of what something like music does to us, is famously ineffable. Transmuting into literature one’s love of a performer has always been a steep task that threatens to shroud or simply shrink in the face of the beloved. And Abdurraqib knows quite well that love may not be enough: “No matter how much our people love us, they can’t protect us.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

One of the subtexts of Little Devil is that Black life and Black performance are almost, if not entirely, equivalent. Indeed, racial identity itself is presented as one elaborate, lifelong performance. For Abdurraqib, as for Baldwin, the two are inseparable. The imbrication of performance and life is familiar territory, too, for readers of theorists like Saidiya Hartman and Fred Moten, who suggested that the improvisation required of Black life was not unlike jazz or the freestyle. If not in such lofty terms, Abdurraqib makes a contribution to this discourse with his latest collection.

This is, I think, an intellectually tricky framework. A certain cynicism could accompany such a view of life-and-death-as-performance, one that would tempt critically attuned minds like Abdurraqib’s into treating intimacies as aesthetic postures. If everyone is putting on an act, how could a person live fully, with a sense that their relationships were real and worthwhile—not merely objects of interpretation? But if Abdurraqib does not come across as a cynic, it is entirely because of the ubiquity of his earnest narration. His highly sincere style recalls Black poets like Ross Gay and Lucille Clifton, whose celebratory incursions are a salve for Black mourning, and a rebuke of its easy ubiquity in representations of Black life. As with the works of these writers, the essays fulfill a timely desire for literature that can console. Abdurraqib’s ebullience for pop culture and history is meant, similarly, to feel infectious—after all, as long as the job is done well, the care a writer takes with the subject can alchemically become our own. To artfully induce surprise while conveying one’s adoration proves difficult all the same, and Abdurraqib’s insights about such well-known cultural figures are more often straightforward and agreeable explanations rather than opportunities for close attention and careful use of rhetoric to speak for themselves.

This is most clear when Abdurraqib feels the need to anticipate political criticism. On Josephine Baker’s work as a spy during World War II, he writes, “I have no interest in weighing the morality of Josephine Baker with regard to this participation.” In a later essay on Beyoncé’s Black Panther–themed Super Bowl show, he likewise “want[s] to be clear in saying that the aesthetics of revolution tied to the violent, capitalistic machine of football…is a far cry from any actual revolutionary work happening in marginalized and neglected communities.” Such apologies for one’s own subject matter can cause a writer’s voice to lapse, besides often doing less to clarify matters than they suggest on first reading. “Performative” also bears a negative connotation, and one that could justly be applied to talented, influential, and ostentatiously wealthy Black artists who don the mere semblance of a radical, redistributive ethos like that of the Panthers. Since Abdurraqib’s premise is celebration, the famous denizens of Little Devil can grow to saintly proportions that deny the book a wider moral, aesthetic, or psychological range. When Abdurraqib is occasionally willing to dress the legends down, he can be funny, as in an essay on Whitney Houston’s 1980s forays into a sort of pop respectability. One suspects that, in an era of global celebrity and its spectacles, Abdurraqib’s examination of such noted virtuosos as Beyoncé and Houston serves as a relatable entry-point for his themes, if not a particularly novel one.

More intriguing and enlightening are the sections wherein Abdurraqib turns nostalgic, perhaps because some of the legends he writes about loom paradoxically larger in their remoteness from our own time. In fact, an interest in the iconography of the 20th century defines much of the book. Soul Train, Aretha Franklin, James Brown, blackface, and Blacks-in-space come to the fore of his mind. Aside from Beyoncé, contemporary expressions of “Blackness” like trap music and memes are by and large not Little Devil’s touchstones. By adopting a historiographical approach, Abdurraqib expands the range he offered in earlier collections, which found much to discuss in contemporary phenomena like hip-hop. Here, stretches of meticulous research exhume fascinating figures like Ellen Armstrong, a relatively unknown Black woman magician who toured with her own show throughout the early 20th century. The ironically unsung lives of Black performers like Armstrong and Merry Clayton (who sang alongside Mick Jagger in “Gimme Shelter”) prompt a rueful contemplation of how talent and personality do not always confer access or notoriety, much less when an artist happens to be Black.

In sections like these which cover relatively unknown artists, one often desires more straight reportage to supplement the book’s predominantly lyrical style. These sections, along with prose-poetic interludes titled “On Times I Have Forced Myself to Dance,” embody what can be both exciting and frustrating in the lyric essay as a genre: the reliance on affect, memoir, and leaps of association to construct meaning. With Abdurraqib’s instinct toward fragmentation, precision (and all that makes his subjects memorable) can be lost, along with an accurate representation of the sensuality, obscenity, and risk that drive so much of Black performance. The book’s second to last chapter, on the Black punk band Fuck U Pay Us, begins with every indication of a great profile—or inspired remixing of the archives—about one musical context in which Blackness is especially fraught, underappreciated, and subversive. The piece expands instead into Abdurraqib’s folksier observations about punk shows and Black anger, without returning to FUPU’s aplomb as performers.

Abdurraqib’s inspiration for A Little Devil’s title was an utterance by one of its subjects, Josephine Baker. The endlessly mythologized expatriate performer—the “Bronze Venus,” the “Creole Goddess”!—said at the 1963 March on Washington that “I was a devil in other countries, and I was a little devil in America, too.” Like so many of the involved parties at that demonstration, the “little devil” statement has been obscured by the long shadow of Dr. Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, which immediately followed Baker’s remarks. Reading Baker’s words now, one notices an almost gendered contrast. King, in our memory, is the soaring, percussive minister whose words had the power to indict the country for its failed idealism, whereas Baker’s oratory is sly and anecdotal, by turns self-deprecating and self-assured. Playfulness, seduction, artistry, and reinvention: Abdurraqib wants us to know that these devilish gestures have their place, too, among the saints that line the corridors in this tiresome, captivating, and essential struggle.